Fionn Folklore Database

For this month's blog post, we're going to be taking a look at the Fionn Folklore Database, giving a brief introduction to it and some of its features and how I, as both a researcher and a social media assistant for the database, use them to my advantage.

First off: As a disclaimer: I do receive financial compensation for my work on the Database, with me being paid on an hourly rate. That being said, for this post, I have deliberately chosen not to use any time tracking services and to avoid any compensation. This is me writing this as someone who is on the database at least once a week, has genuinely found it useful, and wants to help other researchers at all levels get something new out of it, not just for the sake of propping up a project I'm writing on.

So, what is the Fionn Folklore Database, what does it contain, what does it do?

The Fionn Folklore Database is, per its own social media blurb, "a trilingual database connecting people with c. 3,500 folktales and songs about Fionn mac Cumhaill and the legendary Fianna." It organizes over 3,500 different variants of Fenian material from everywhere from Fionn's familiar haunts of Scotland and Ireland to The Isle of Man, England, Canada, and the USA, making it a one-stop shop for all things relating to the Fianna as they survive in the oral tradition. Via the database, it's possible to locate the exact archive that each attestation is currently held in, whether it is currently online or not, the informant, the interviewer, the language it was recorded in, the location, and, occasionally, a summary.

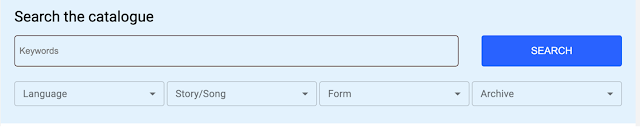

The first thing you will see when you go on the website will be a search bar that indicates several different parameters: keywords (for when you know, roughly, what you might be looking for, even if you might not know the tale types), language (for when you are looking for stories in a particular language), story/song (for hunting for individual tale types), form (to specify if you're looking for a lay, a waulking song, a game, a story, etc.), and an archive (to highlight material found in a specific archive.) This is incredibly useful if you know, at least roughly, what you're looking for and you want to refine your search to fit that.

Going to the upper section of the toolbar, clicking on the “English” section will give you the option to choose between English, Scottish Gaelic, or Irish. Selecting the Irish, mar shampla, will give you the option of displaying the archive like this:

On a personal level, most of the time, I choose to go directly to my own favorite section of the archive, "stories and songs", where you will see an overview of all currently categorized Fenian tale types, with the database currently recognizing, by my last count, 220 different individual Fenian tale types, which range from very well-known Fenian tales like the story of Fionn and the Salmon of Knowledge, Diarmuid and Gráinne, or the story of Oisín and Niamh, to stories that are lesser known, such as "Laoi Cholann gan Cheann" ("Lay of the Headless Body") , in which Oisín marrries a woman who, in at least some variants of the story, is headless; Fionn, Oscar, agus a'Phapa (“Fionn, Oscar, and the Pope”), in which Oscar steals a sword from the Pope (in all fairness, he DOES have a good reason for it!); and "Rás Shliabh na mBan Finn" ("The Race of the Hill of the Women of Fionn"), in which Fionn decides that, naturally, the best way for him to select a wife is to have all interested parties compete in a foot race (even though his top pick for the role is, naturally, Gráinne).

Story types can include everything from international tales (making it useful to anyone who might be studying, say, the Dragon Slayer motif in its international context) to lays to lullabies to seanfhocals to games. Each entry is named according to the language that it is most prevalent in – so if a story is more prevalent in Scotland, you will see it listed in Scottish Gaelic; if it is more prevalent in Ireland, it will be in Gaeilge.

While everyone has their own strategies for doing this sort of thing, and everyone has their own research interests, I personally take the approach that got me into the field in the first place as a teenager: Diving in, looking through the list for tales that seem like they might be interesting, and exploring from there. It can be a lot of fun to see what's out there and to see how varied the tradition truly can be, and it's a fun challenge each week to try to figure out what I'm going to bring out, what might surprise people, what might make them laugh. (The musical choices are my own, though. For better or worse.) I never know what I'm going to run across on a day-to-day basis and there's still a lot for me to find out. My approach is not for someone who wants to do a systematic study of the material, but for anyone who is just dipping a toe into Fenian material for the first time, I think that it's a fun way to explore the material. My process for writing the script for a reel usually takes four steps: The first is finding a story – I usually have a couple in the back of my mind that I’ve scouted out ahead of time and think might be good material, then I write down, by hand, a summary of the basic plot points of a story after re-reading it, then I simplify it to easily fit into a few slides on a reel, and finally I put that last script onto the reel itself, which is then accompanied by photos (this is the part that generally takes the longest, because it isn’t like there’s an over-abundance of pictures of Fenian material), music, and a liberal use of the crop and zoom feature on Wondershare. This way, the audience can get the general gist of a particular story within about 30-45 seconds. (I do not recommend this strategy on long hero tales.)

Suppose that you are going to the Database with a specific goal in mind, though. Suppose you don’t want to dip a toe in and explore it by specific tale types. The Database can accommodate that!

A feature that I use relatively little because of the nature of my research, but that I find fascinating on a technological level, is under the “places” category, where it is possible to view an interactive map where you can narrow it down to discover exactly where a folktale was recorded. This is very useful if you’re doing work for a Heritage project or if you’re doing an analysis of folklore from a specific area (suppose, for example, you were doing a paper on folktales collecting purely from Co. Cork, or on the Scottish Fenian tradition, or, on the Fenian tales collected from Cape Breton – this is useful for that sort of research, and it can be fascinating to see where stories have been collected and what kinds of stories might have been collected from a specific region.)

Likewise, if you’re doing work on a given tradition bearer’s repertoire, or if you’re assigning work on a given tradition bearer’s repertoire (as I’ve sometimes been assigned for folklore classes in the past), the “people” section allows you to find an individual storyteller, listing all known biographical details we have about a given tradition bearer, as well as all known Fenian songs in their repertoire, sorted by their first name. You can see here that I’ve selected Peig Sayers from the list, since she’s a very well-documented tradition bearer with an extensive repertoire. We can see here the years that she was alive, her country (Ireland), her province (Munster), her county (Kerry), and her barony (Corcaguiny), and her village (Vicarstown). For some tradition bearers, we don’t have that degree of knowledge, but we always try to fill in whatever we have. (And, of course, we welcome any further knowledge!)

We can see under her name that, as an interviewee, she has nine entries in the database, four instances of “An Óige, an Saol, agus an Bás” (Youth, the World, and Death), three instances of “Macghníomhartha Fhinn (Fionn’s Boyhood Deeds), an instance of Àireamh Muinntir Fhinn agus Dhubhain (“The Enumeration of Fionn and Dubhan’s People”), and one combined instance of “Na Fir Ghorma” (“The Blue Men”) and “Fionn sa Chliabhán (“Fionn in the Cradle.”) Each link will take the user directly to a given story’s entry, giving further details on the archive it is currently housed in, the page numbers of the citation, the word count (when avilable), the collector, and any other relevant material.

Lastly, suppose that you are making an appointment to visit a specific archive, or you only have access to a single archive – that is when you go to the last option on the toolbar, fittingly entitled “archives.” The Fionn Folklore Database does not, in and of itself, store stories on our database, but we can point you out to where you can go to get access to them, whether it’s online or in person.

In my case, I might want to see what Harvard has available, so that I can explore it whenever I have the chance. I will instantly see that there are two options if I click on Harvard: the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, at Widener Library, or the Charles Dunn Collection, in the Harvard Library Depository. It’s more personally convenient for me to go to Widener, so I chose to select Widener.

There are five entries for this location, all of them collected by Roslyn Blyn-LaDrew on Augsut 30th, 1974. As with the “people” section, clicking on any individual entry will give you more information on the tradition bearers, the citation for the location in the archives, the recording length, the language of the recording, and anything else. This is a great resource if you’re planning a trip to an archive and want to strategize what to request ahead of time!

The very last tab contains miscellaneous bits of information – a guide to the different people involved in the creation of the archive (including yours truly), a guide to navigating the database (if this long spiel wasn’t enough), a guide to common characters that show up in Fenian stories, and a glossary, which includes both terms that pop up regularly in Fenian material (like the “ball seirce” that Diarmaid has in multiple stories) some general folkloric terms (“What is a ‘tradition bearer’?), and some general Fenian terms (“What is the Fianna? What is a ‘cycle’? Who is ‘James MacPherson?’” Even though a better question might of course be “Why is James Macpherson?”) If you’ve been involved with Fenian stuff for a long time, or even the general world of Irish or Scottish folklore, you might not ever have to see this page, but everyone has to start somewhere, and not everyone coming into the Database is going to have the same level of knowledge. There is also a section, written by Natasha Sumner, which goes into the process that went into creating the Database, describing the background of it as well as the methodology, as well as a link to citing folkloric sources. We generally recommend people cite according to the style of the host archive, if there is one, instead of just citing the Fionn Folklore Database; everyone working on the project would love for it to be available forever, I know I certainly would, but anyone who has been in the world of online sources for Celtic Studies knows just how fragile these things can be.

That is really it for the Fionn Folklore Database – I dearly encourage everyone to dive into it and see what they can find, I know that the last few months working on it has really opened my eyes to the full scope of the folkloric tradition and how much isn’t put into general Fenian stories for children (often for good reason, admittedly), and it’s something that, even beyond my personal involvement with it, I’m very passionate about and I’m really excited about.

Besides the website link, which I included in the first paragraph and am including again here, we can also be reached on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, the latter two where I try to put out reels each week highlighting a story from the “Stories and Songs” section, and where Pádraig Ó Mathúna, my colleague on the project, regularly posts updates of any talks and events we’re doing, as well as a “Seanfhocal na Seachtaine” each week that highlights some of the different seanfhocals that are featured on the database.

Rachel Martin

Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures

Harvard

Comments

Post a Comment